By Linda Whitmore

The threads of one Silverton family’s story run through the quilt of Oregon history. The Geer family – in addition to being among the few today who can trace their genealogy to the earliest settlers – has the unique distinction of still living on the farm their ancestors settled.

As Oregon celebrates its 150th anniversary of statehood this week, Vesper Geer Rose, 91, and her nephew, Jim Toler, tell their family’s tale while sitting by the woodstove in the kitchen of GeerCrest Farm in the Waldo Hills.

In the early 1800s, Indians of the region had been joined by few white pioneers. There was no established government or law, and the need was evident. In 1843, a few American settlers who had come by wagon the year before and some retired Hudson’s Bay trappers gathered at trading post at Champoeg to vote whether to establish a territorial government.

“Someone drew a line in the dust with a stick,” said Vesper Rose. “Joe Meek did that,” said Toler, a Geer descendant who has encyclopedic knowledge of the family’s history.

The vote was taken by standing on either side of that line. Forty-nine men moved to the “aye” side and 49 stood against organizing, with the two Frenchmen still deciding. Their vote led to alignment with the United States.

Meek took the news back to Washington, D.C. that there was an independent government interested in having Oregon become a U.S. territory.

“That got the attention of a lot of people,” Toler said. “One was Joel Palmer in Indiana … He had heard how remarkable it was in terms of fertility and climate. So in 1845 he set out on the Oregon Trail. In that wagon train was a young man named Fredrick Geer. He was one of several grown sons of Joseph Geer.

Fredrick had the unfortunate experience of making a bad choice when they got to Ft. Boise in Idaho.”

There near the fort, part of the group decided to divert on what they’d been told was a shortcut that would avoid crossing the Blue Mountains and traveling by raft down the Columbia River. Fred Geer, in his 20s, was among those who took the detour.

“Their story is called the Lost Wagon Train of 1845,” said Toler. “They endured incredible hardships and at one time were hopelessly lost in Central Oregon.”

Those in the main group sent out a search party that rescued them and led them back to The Dalles. Many miles later someone saw gold nuggets in a child’s bucket. The boy said he’d found the gold while they were lost. Through the years many people have searched but the location was never again discovered and the story is known as the Blue Bucket Mine mystery.

When the emigrants arrived at their destination, Fred Geer established his homestead near Champoeg. He went to work with other new arrivals, Sam Barlow and Joel Palmer, building a road that would avoid the dangerous rafting section of the journey by passing on the south side of Mount Hood. The route became known as Barlow Road. The new, safe route opened the floodgates to followers.

“Fred had sent word back to his father, Joseph, to sell the farms as fast as they could – all the stories about Oregon were true. It was the Eden of the West,” Toler said.

Palmer went back east in 1846 to organize a wagon train, which included several Geer family members. “Joseph was in his 50s. He brought his wife, Mary, and oldest son, Ralph, a nurseryman in Knox County, Ill., and his wife, Mary, and their four children,” and others.

The wagon train stopped near Umatilla where it was met by missionary Marcus Whitman. Some of the party decided to winter at the Whitman Mission “and their history is written in blood,” Ralph Geer wrote in his account of the journey for the Oregon Pioneer Association in 1879.

The wagon train stopped near Umatilla where it was met by missionary Marcus Whitman. Some of the party decided to winter at the Whitman Mission “and their history is written in blood,” Ralph Geer wrote in his account of the journey for the Oregon Pioneer Association in 1879.

The Geers, however, were among the group that plodded on. They traveled the Barlow Road the first year it opened. Their six-month journey came to a rest near what is now Riches Road outside Silverton where Ralph’s wife, Mary, had a relative, David Culver, who had come earlier. “Culver was away when the Geers arrived in ’47, so they overwintered in his little cabin,” Toler said.

Erika Toler added, “Mary traded ribbons and buttons with the Indians. That got them through the winter.”

“At the time the Geers settled in Culver’s cabin the Klamath Indians came to this area to winter with the Molallas,” Toler said. Relations with the Klamaths were not always easy, however. “They were was particularly aggressive band of Indians and made the settlers very nervous. One particular Indian, Crooked Finger, was kind of a war chief.” Crooked Finger’s men were said to have gone to the settlers’ farms and forced women to make them meals, which caused great concern among the men, who had to leave their women alone while they worked.

“The settlers went to the Molallas and told them the Klamaths had to go home. The Molallas either weren’t willing to tell or the Klamaths weren’t willing to go, so the settlers formed a militia,” Toler continued. “Dan Waldo was appointed colonel and Ralph Geer was appointed captain.” The militia divided into two forces with the cavalry led by Waldo and infantry by Geer.

“They encountered the Indian camp along the Abiqua River and there was a skirmish. It is told that two Klamaths were captured and an old Molalla chief was killed.”

The Indians withdrew up the river and were pursued the next day.

“According to Ralph Geer’s writings, he wasn’t there the second day,” Toler said. Ralph Geer later said the Klamath Trail passed within sight of his cabin and he had been told Crooked Finger was in the vicinity so he went home to protect his family.

“On the second day, the infantry re-encounted the Indian camp and that’s when what has become known as The Massacre occurred. A number of Indians, including women, were killed. As a result, the Klamaths agreed to go back to southern Oregon.

“This was something that wasn’t talked about for a long, long time,” Toler said.

For the settlers, life returned to normal. Ralph Geer was asked to teach school, so he and the others built a school house.

He had brought from Illinois “a bushel of apple seeds and half bushel of pear seeds,” which he planted on the nearby Daniel Waldo homestead. The young trees became root stock for grafting.

In 1848 a neighbor, William Parker, who had heard about the discovery of gold in California, decided to seek his fortune. In those days, no deeds were written or recorded but he signed over the squatter’s rights for his 640 acres to the Geer family – this farm became known as GeerCrest.

The family expanded Parker’s cabin and traded their root stock to Henderson Lewelling for grafting wood. Today Lewelling is known as the father of the Pacific Northwest orchard industry. Fruit was shipped to California where it was a precious commodity for the Gold Rushers. The Geer family prospered and was able to build a new house – the one where Vesper Geer Rose and the Tolers now live.

“Today this house is considered the state’s oldest frame construction residence that has remained in the same family,” Toler said. The 1851 GeerCrest farmhouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

Construction was well under way when its doors, which were shipped from the East Coast around the Horn, arrived at the site. But there was a problem, they were too small for the doorways. Today one can see where each door was modified to fit the frame.

One of Ralph’s children, a daughter named Florinda, married Timothy Davenport. She died when her son, Homer, was a boy so he spent much of his youth at his maternal grandparents’ home, GeerCrest. When grown, Homer Davenport went to New York City and became a nationally renowned political cartoonist. Later he returned to the house and drew a cartoon on the exterior wall. It can still be seen, along with the words of remembrance he penciled there.

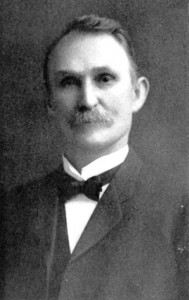

Ralph Geer’s brother, Heman, was also a nurseryman. In the 1860s, he sold his Silverton Hills farm, where his son, Theodore Thurston (known as T.T.) Geer, had been born and moved into town.

“For a period of time he had a nursery business in Silverton,” Jim Toler said. “He probably is the one who built (what is now known as) the Coolidge house. When his family moved out, he sold it to Ai Coolidge.”

Heman and his wife, Cynthia, separated and the boy T.T. had to quit school and move to the home of his cousin, Cal Geer, (Ralph’s son) in the Waldo Hills. He worked for a living and studied on his own.

He later served in the Oregon State Legislature for several terms and became Speaker of the House. In 1899, he was elected the state’s 10th governor

– the first native-born Oregonian to hold the office.

Through the years many members of the Geer family have lived at GeerCrest. Its large living room has been the setting for festive gatherings and many meetings.

“Early Silverton was a hotbed of politics. In the days when Oregon was a territory a lot of Silverton names were involved in government,” Toler said. In the early 1850s, Ralph Geer was among the men who founded Oregon’s Republican Party and “some of those meetings were here.”

Ralph Geer was elected territorial representative in 1854.

After Ralph died, Chet Geer, son of L.B Geer, moved onto the farm and remodeled the house.

Chet’s brother, Arch, moved in after he married in 1916. It was here that Vesper was born. The family moved to Salem so she could attend high school there and her mother, Gail, could work as a nurse. Renters moved in and “the house fell into disrepair,” Vesper Rose said. Arch Geer – her father and Jim Toler’s grandfather – made repairs in 1960.

The Columbus Day storm of 1962 destroyed the family’s Salem house so the Arch Geers returned to the farm and Toler came to live with them. After graduating from Silverton High School, Toler moved on. He returned in 1999 and with his wife, Erika, did structural restoration in 2001 but much of the house remains as it always has been.

Through the years, the crops and the people of GeerCrest Farm have changed but the family’s history surrounds them. On the walls are pictures of a former governor, a drawing by a famous cartoonist, the furnishings span the years and include a table, rocking chair, quilt, small box and sewing machine that came across the country in a covered wagon.