This is the third segment

This is the third segment

in a year-long history series

Our Town is publishing to commemorate Oregon’s Sesquicentennial. This story relates to the daily lives of the native population who lived here before white settlement. There will be a sequel next month about a decisive battle that took place along the Abiqua River.

By Linda Whitmore

As Oregon marks its 150th year of statehood we hear numerous accounts of the rigors pioneers endured, but of course, these white settlers were not the first to dwell in the region. Indigenous people had lived here for perhaps thousands of years.

Among them were members of the Molalla and Kalapuya (spelled variously Calapooia, Calapuya, Calapooya, Kalapooia and Kalapooya) tribes.

According to Robert Horace Down, who wrote A History of Silverton Country in 1924, the area north of Silverton had been inhabited by Molallas – a “Waulalpulan” tribe – and south of Silver Creek were Calapooias whose hunting grounds went across Howell Prairie to the Pudding River.

As for the Molallas, an 1879 publication called The West Shore, reported that “The Northern, or Upper or Valley Molallas … had winter villages from their legendary birthplace near Mount Hood to present day Oregon City, and just east of Salem to the foot of Mount Jefferson.”

But by the time of the influx of American settlers – which began in the late 1840s after Oregon became a U.S. territory and grew with the offer of free land for homesteading – the native population had already significantly diminished. Down wrote, “Their numbers were greatly reduced by the mysterious epidemics of 1824 and 1829, which swept away perhaps four-fifths of Indian population of Columbia and Willamette Valleys.”

But by the time of the influx of American settlers – which began in the late 1840s after Oregon became a U.S. territory and grew with the offer of free land for homesteading – the native population had already significantly diminished. Down wrote, “Their numbers were greatly reduced by the mysterious epidemics of 1824 and 1829, which swept away perhaps four-fifths of Indian population of Columbia and Willamette Valleys.”

The natives had no immunity to the diseases unwittingly brought by first white people in Oregon – the trappers, traders and missionaries. Small pox, measles, and even the common cold, were deadly. According to a report prepared by Silverton residents Quinton and Lois Estell in 1973, when Santiam Calapooias met with U.S. agents in 1851, there were only 65 adult males, 10 boys, and 80 women and girls.

“Because so many of them died before the white man arrived in the Silverton area, little is known about local Indians, however … because of the proximity and based upon artifacts recovered in local areas, plus what was recorded by early explorers, it is assumed the Indians here were much like Columbia River Indians,” the Estells wrote.

The men and women had defined roles in feeding, clothing and housing their families. Work also was done by slaves – people captured during tribal wars.

This region’s tribes did not cultivate land; the men hunted and fished and the women collected and prepared food and cared for the children. A man might have more than one wife, who was acquired by purchase.

Using forked spears and woven nets, the men caught fish in local streams. They used arrows and net traps to hunt game. They also traded widely with other tribes for foods.

The women gathered roots such as wappato and camas, tarweed seeds and fruits and berries, which were eaten fresh and dried for winter.

The men made nets, arrowheads and tools. The women wove baskets, ground flour and dried and smoked fish, elk and deer meat.

During the summer the Molallas lived in shelters of bark and branches. In winter several families would gather in an underground pit home with walls and roof made of planks. Dried fish and meat were suspended from ceiling rafters and dried berries and fruit were stored in baskets – the Molallas had no fired pottery.

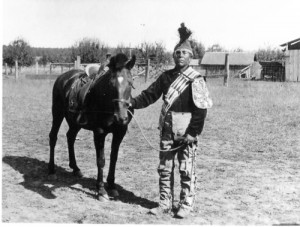

They also made stone utensils such as mortar and pestles, knives, axes, sinkers and awls. Women wore skirts of skin or grass in the summer and donned leggings and robes of fur and skin in the winter, according to Silverton Country History, a report by Mildred Thayer in 1995. The men wore little clothing in summer, and in the winter had leather leggings, capes, moccasins and hats and sometimes buckskin shirts. “Wealthier Indians decorated their clothing with porcupine quills or beads,” Thayer wrote. Other accessories included necklaces, wrist bands, and ear plugs of shells. They often had tattoos and painted themselves with dyes made from plants.

According to Thayer, the natives believed all things in nature had spirits. The hill in Mt. Angel on which the abbey stands was known as Topalamahoh – “the place of communion.” They came many miles to a a small, circular enclosure facing south. Worshippers would look out over the land below as they prayed, according to Down’s history.

The Molallas’ lives were irreparably changed by the coming of white settlers. First, they lost 75 to 80 percent of their population to disease. Their food supply was reduced by competition from settlers armed with guns. The final blow came when their lands were taken by the U.S. government.

The Molallas’ lives were irreparably changed by the coming of white settlers. First, they lost 75 to 80 percent of their population to disease. Their food supply was reduced by competition from settlers armed with guns. The final blow came when their lands were taken by the U.S. government.

In 1851, a treaty was signed with Northern Molallas. The original intent was to move them east of the Cascades, but they refused to go so far from their traditional lands. When the treaty was ratified in 1855, the proclamation was made that all Willamette Valley Indians would be moved to reservations. Smoke Signals, a 1999 special edition publication of the Grand Ronde Tribe, said, “The treaty ceded mountain Molalla land to the U.S. and the band of 30 agreed to relocate along with Kalapuya and Upper Umpqua Tribes to the Grand Ronde Valley.”

Tribe members were not treated well on the reservations and many died. According to Down’s 1924 book, the Molalla population “in 1849 members were estimated at 100. In 1877 there were several families on the Grand Ronde reservation and in 1881 there were 20 people in the mountains west of Klamath Lake.”

An account written by Jeff Brakas in 2004 said, “Frederick Yelkes (Dushwilgushlik, which means ‘hunter,’) born in 1886 is considered the last full-blooded Molalla.”