“I’m ready to die,” she said, turning her head toward the apartment window.

I looked at my mother-in-law, Nadine Stack, not knowing what to say. This was three years ago, and at age 97 she was in good health and still able to get around. She was even a member of the beanbag baseball team at Mount Angel Towers, the assisted living apartments where she lived.

“I’m just ready,” she said. “I’ve had a good life.”

She might have been ready, but I don’t think we were. She had 12 children spread across the country, from Alaska to Arizona to Tennessee to Maine. Two others had preceded her in death. They – we – were a fairly close-knit family, but I don’t think anyone had really contemplated the thought of losing her.

All mothers are special, but Nadine was one of a kind. She grew up during the Depression on a remote ranch in eastern Montana. As a young girl, a bag of barley served as her bed. During World War II she joined the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve. After the war, she married another young veteran from eastern Montana, Charlie Stack. The wedding was in Seattle, and soon after they headed for a new adventure in Alaska and his first duty station with the Civil Aeronautics Authority, the predecessor of the Federal Aviation Agency. Over nearly 30 years in Alaska they lived on Annette Island and in Cape Yakutaga, Nome and Fairbanks.

Oh, yes, they raised 14 children, too.

Despite the challenges and hardships raising a family involves, Nadine never once uttered a negative word. If she did think it, she didn’t say it out loud. The closest I ever heard her get to criticism was to say, “That’s not for me.”

When Charlie retired from the FAA in the 1970s, they built a house on McCully Mountain outside Lyons, Oregon, where they raised sheep and a few chickens. They later lived in Sublimity for a short time and then in Mount Angel.

When COVID appeared, Nadine moved in with my wife Patti and me. She was still in relatively good health, and it was a pleasure having her with us. One of her favorite things was to watch the fire in the fireplace.

One Saturday last summer, I heard her in the living room. She was leaning over the fireplace trying to start a fire. I reminded her that it was going to be in the 70s that day, so a fire might be optional. She turned to me and couldn’t talk. Rather, she could only say a single word: ”Three.”

We bundled her off to the emergency room, hoping the doctors could figure out how, overnight, she could lose her speech.

After tests and consultations, one of the doctors said the culprit appeared to be a small brain bleed near the speech center. He couldn’t say for sure, but he conjectured that over time the problem would go away. For further studies and observation, he suggested she be hospitalized.

After a couple of days, she came home from the hospital. Sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, descended on our house. They had only one concern: to provide their mom with the best care possible. They had no way of knowing how long it might be, but they committed themselves to the long haul.

In the meantime, she regained her speech, just as the doctor had thought she would. But ultimately she began to fade.

Then something amazing happened. Waves of unrelenting love rained down on her. Sons and daughters, grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins arrived to visit and help as her health continued to fail. For nine months they kept it up. There was rarely a time when someone wasn’t here helping to care for Nadine.

During this time we all received one last gift from Nadine: This close-knit family became a single unit. We shared not only the work and worry of caring for her and staying up with her through the night, but we also shared ourselves as she made one last journey.

On March 22, at 11:15 a.m. Nadine Stack – mother, friend, neighbor and the touchstone for generations of the Stack family – died quietly. She was 100 years old. With her were Patti and two brothers, Kevin and Damian, and Kevin’s wife Jackie and their grandson, Jayden.

When it happened, they and their other brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, were finally ready, too.

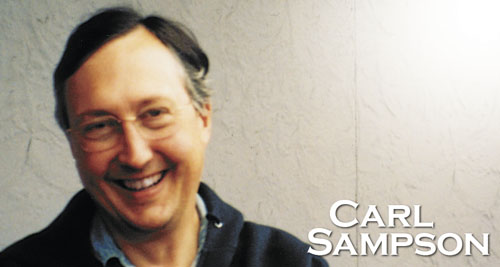

Carl Sampson is a freelance editor and writer. He lives in Stayton, Oregon.