By Audrey Nieswandt

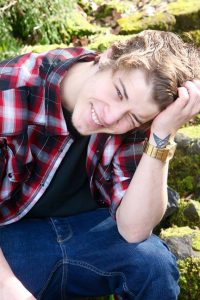

My son, Roman Emmanuel Mark Lauzon, died last month at the age of 20. Roman was bright, artistic, athletic, kind-hearted and handsome.

He also was an addict.

“The loss of your son is huge,” my counselor said. “And his death is complicated by the way addiction is perceived. If he had died from cancer or heart disease, the sympathy and outreach would be different. But addiction? Most people don’t understand or may silently judge him – and you.”

Addiction kills. I live this reality. Daily, I am slowly, unwillingly, absorbing a loss that is the hardest any parent can bear.

Roman came home for help. He wanted to change his life. Two weeks prior, he drove from Seattle to Silverton.

Roman enrolled in college classes. He reconnected with old friends, and they hung out, playing video games, talking, laughing.

That last night, Roman said he was going out.

Be home at a decent time, I mandated.

I will be, he promised. Love you, mom.

What I didn’t know: that night would be his last.

Sometime that evening as I slept, Roman downed tranquilizers, alcohol and a synthetic opioid. The mix was fatal. Roman never woke.

It’s harder to describe what else died with Roman.

The night Roman died, so did his future business degree; a marriage to his beautiful girlfriend; his potential children; eventual contributions to school, community, friendships, and workplace; his music, artwork, and perennial smile.

Part of me perished as well. His death left a crater in my heart filled with dark sorrow.

Addiction kills.

Since 2014, drug overdoses have claimed the number one spot in accidental deaths, overshadowing even car accidents (National Safety Council).

Young adults ages 19 to 25 are at the greatest risk for overdose, and males are 2.5 as likely to die as females (Trust for American’s Health).

Between 2000 and 2013, youth (ages 12 to 25) overdose rates more than doubled in 18 states including Oregon, more than tripled in 12 states, and more than quadrupled in five (National Survey on Drug Use and Health).

“Addiction is a chronic disease of the young,” Dr. Nora Volkow asserted (National Institute on Drug Abuse).

Indeed, its prevalence renders it a major public health problem, charting like some new infectious disease.

Unfortunately, the public tends to see addiction as a moral or personal failure rather than a treatable disease, a fact that may explain our national reluctance to treat its ravaged populations.

Nationally, only one in 10 addicts receives any type of treatment. Oregon numbers are slightly better: 14 percent are treated, 86 percent are not.

Addiction carries the weight of censure and the burden of shame. “Addiction is a dirty word,” Steve Comella, addictions specialist, remarked. “Due to its association with drugs, crime, violence and the legal system, it is often seen as a moral failing, not a medical issue.”

In fact, while professionals classify addiction as a disease resulting from genetic, neurobiological, behavioral and environmental causes, substance use disorder is viewed by up to 80 percent of the public as a personal failing, one that indicates a lack of willpower, character or discipline (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Young people are especially vulnerable to addiction’s grip: 90 percent of adults with severe substance use disorder began illicit drug use during early adolescence (12-15). Problematically, early drug use can permanently alter the young and malleable brain.

While Roman’s overdose came as a horrific shock, his death resulted from a progressive systemic failure to recover a young person from addiction’s iron grasp.

Taken separately, these individual failures can be argued and rationalized away. Cumulatively, however, these personal, family, community, medical and societal failures fomented a perfect storm that resulted in Roman’s death.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of marriage. His father left the home when he was 12. Within six months, my ex moved out-of-state, and I reentered the workplace with little familial support.

With two younger children in the household, I struggled with Roman as a single mom for three years, then sent him to Seattle. There, he was frequently unsupervised as his father traveled on business and worked long hours.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of family. Though Roman had relatives nearby, no one consistently reached out to assist, advise or mentor him. Others never acknowledged his issues or offered to help. Some banned Roman from their homes.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of a stigmatizing school system. For a good chunk of his education, Roman was marginalized as one of the “bad kids.” Roman was bright but impulsive.

By second grade, teachers had difficulty controlling him and he was frequently penalized for his behaviors.

By fifth grade, Roman was diagnosed with ADHD. In eighth grade, Roman was expelled. By his freshman year in high school, Roman resisted any rules I demanded; exhausted and concerned, I sent him to his father. He attended high school near Seattle, later completing his diploma in an alternative setting.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of community policing. At 13, Roman received his first citation for smoking marijuana at the park.

Shaken, I asked the officer what to do: “Don’t worry,” he said, “The courts are so backed up, he’ll probably just get probation.”

At 16, Roman returned to Oregon for the summer. I phoned the police; as a sole woman and single parent, I wanted reinforcement. An officer arrived and I relayed my concerns. We had a good conversation.

The night of Roman’s death, that same officer stood with a row of others in my driveway. “I remember you,” I said. He nodded.

Three days later, grieving, I asked to meet with the chief of police. What had happened that night? I inquired. “Looks like a death from overdose,” he said, voice matter-of-fact.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of the treatment community. At 13, I sent him to a counselor specializing in adolescence. Once in Seattle, counseling lapsed. In 2015, when the magnitude of his addiction became apparent, Roman returned to Oregon.

Three times a week, we drove to the Portland De Paul Center for outpatient treatment. We waited on an in-patient bed that never appeared.

You’re on the waiting list, we were informed.

How long? I asked.

Four weeks, six weeks, maybe longer.

Impatient, Roman returned to Seattle. Frustrated, I researched NA groups near him. Roman went but his attendance petered off.

When he returned home, I immediately scheduled an intake and six consecutive appointments with an addictions specialist. Roman’s first visit was Monday, the day after he overdosed.

Roman’s overdose was partially a failure of society, one in which young men frequently cannot find their feet or bearings.

In this world, young men are particularly at risk for any number of tragedies: injury, unemployment, suicide, and overdose, among others.

When young men leave the educational system and face large decisions regarding school, career, and family, they are at the greatest risk of falling deeply into substance abuse (Evidence-based Prevention and Intervention Support Center).

Mostly, Roman’s addiction feels like my failure.

“He came home to you,” my counselor asserted.

Yes, he did.

Roman came home and I could not stop his drug abuse, could not solve his underlying issues, and could not rescue him from an early death. He came home, where he found acceptance, support, laughter, and love, but not even the greatest of these could save him.

Only a mother who, like me, sits in her chair, gazing out the window at autumn’s golden, spinning leaves, can begin to understand. Only a mother who has lived through endless nights of worry, prayer and hope, one who has fearlessly loved her addicted child, one who has been moved by great anger, joy, and sorrow, only one who has kissed the cold cheek of her dead son: only this mother can begin to fathom the depth of my grief.

Small towns are wonderful. Though not a native, I have come to call Silverton home. Here, I have seen people converse, connect and create community. I also have heard them gossip, ostracize and judge. Small towns look closely but also look away; they both invite and exclude. Like anywhere on this globe, people here inhabit the best and worst of human nature.

Roman was a Silverton kid. He was one of mine, but also one of yours. I write these words and broadcast my pain not to divide, but to urge examination.

Roman could well have been your nephew, neighbor, student, son. In a way, Roman is all boys who struggle, who hurt, who seek what they do not find, who fall and rise and fall again; those kids are everywhere. Most certainly, they live here.

The night Roman died from a fatal overdose, his younger brother gazed out the window at the dark sky. “Mom,” he said. “I think I see Roman’s star. It’s the biggest one in the sky, and tonight, it’s shining so, so bright.” Thus did Roman’s Star Foundation gain its name.

The goal of Roman’s Star Foundation is to connect with youth who are struggling with addiction issues. The foundation will work with youth, parents and the systems to educate, address and curtail the public health issue of illicit drug use and overdose fatalities.

Donations, volunteer assistance, queries, or public speaking requests are welcome. Please email [email protected] or Roman’s Star @530 Edgewood Drive in Silverton, OR 97381.

Roman died of his addiction. While writing, I struggled with how much to reveal, which details to divulge. Mostly, I struggled with the seeming purposelessness of my son’s death.

But perhaps meaning can be discerned: if one child, brother, neighbor, or grandson can be saved, then a purpose is achieved. If only one individual is touched by my words or moved to action, then Roman’s death was not in vain. Roman would want this: he was a vibrant, edgy, charismatic kid who always pushed the limits. May my honesty honor his young life, and ennoble his tragic death. With a breaking heart, I offer these words as my final gift to this bright and beautiful boy, my son, my Roman.