By Kristine Thomas

Silverton resident Dawn Tacker doesn’t want any parent to feel like she did when she received the news both of her sons were dyslexic this spring.

“I was in tears,” she said. “It was a huge reality check. I felt terrible that we didn’t recognize Andrew was dyslexic and didn’t catch it until he was in the seventh grade.”

That’s why she learned everything she could about dyslexia. Now a dyslexia specialist, she wants to share her knowledge about dyslexia with parents and educators.

“No one should go through what we went through learning our 12-year-old son is dyslexic,” Tacker said. “I am here to prevent that. We knew he had been struggling since he was in second grade, but despite our best efforts and expert assessments, we didn’t find the answers until six years later.”

If it hadn’t been for her youngest son’s preschool teacher, Stephanie Freeman, noticing Phineas had several signs of dyslexia, Tacker would have never learned her oldest son was dyslexic too.

“It was hard to identify our oldest son because he loves to read and he’s a strong reader,” Tacker said. “He’s what is called a stealth dyslexic. He does struggle in writing, spelling and math.”

October is National Dyslexia Awareness Month. Traverse Dyslexia, Tacker’s organization, will be sponsoring an informational display on dyslexia at the Silver Falls Library from Oct. 15 to Nov. 15 and a presentation Nov. 10, 7 p.m. at the library.

Tacker said one in five people or 20 percent of students in America are dyslexic.

“Sometimes, it is really obvious a student is dyslexic,” she said. “They usually hit a wall in second or third grade. That’s when a student has to move from learning to read to reading to learn.”

Dyslexia looks different from person-to-person, Tacker said, adding dyslexia is 100 percent genetic. Tacker said she or her husband, Dave, or both are probably dyslexic and she sees evidence of it on both sides of the family trees.

With a bachelor’s degree from American University in Washington D.C. and her master’s degree from Georgetown, Tacker said both she and her husband place an emphasis on the importance of an education.

When she heard the word ‘dyslexia,’ the first thought she had was all the roadblocks that would hinder her sons from receiving an education and achieving their potential. At first, she said, she was “totally overwhelmed by the news.”

What she learned was she couldn’t be more wrong about what she thought she knew about dyslexia.

Tacker spent the summer becoming a dyslexia specialist, meaning she can screen students to see if they are dyslexic and then develop a roadmap for interventions and classroom accommodations.

Her qualifications include 48 hours of graduate coursework in Screening for Dyslexia taught by Susan Barton, who is an expert and developer of the Barton Reading and Spelling System; 150 hours of additional training and study in dyslexia assessment, neurobiology, reading interventions and more. Tacker said dyslexia is a physiological brain structure difference that is inherited. It results in challenges with reading, spelling, and/or math despite average to superior intelligence. Dyslexia exists alongside many strengths and natural abilities.

What she has learned is dyslexia becomes a problem only if it isn’t addressed.

Dyslexic children need evidence-based interventions to learn to read, write, and spell more efficiently, Tacker said, adding the only proven methods of interventions for dyslexia are systems based on the Orton-Gillingham method.

Tacker said dyslexic students require classroom accommodations to allow them to access the same curricula as their neurotypical peers. For example, instead of asking a dyslexic student to hand write an assignment – even a worksheet – there are ways it can be done using a computer. Ask a dyslexic student to read a book and he might struggle to comprehend its meaning. Let the student listen to an audio version of the book and he’ll correctly tell you what it was about.

After empowering herself with information, she now knows what steps to take to help her sons. “I now have a lot of hope,” she said. “I know what to do.”

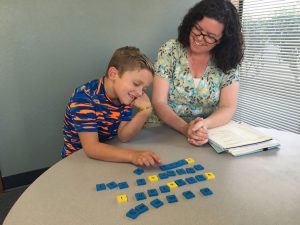

Tacker works one-on-one with each of her sons, who are in the seventh and first grade, at least two hours a week year round. By devoting 18 to 36 months to dyslexia tutoring, Tacker said her sons will develop the tools to be successful in school and life.

“The brain of someone who is dyslexic looks different,” she said. “Reading and language processing involves many areas of the brain. These skills rely on the highways between these areas. In the brain of someone who is dyslexic, there are roadblocks and detours on these highways. A dyslexic brain may process language by taking a mile-long detour, while a typical brain might only need to travel a block to complete the same task.”

There are interventions to help a person with dyslexia to become more efficient. The key is the earlier the intervention, the better for the student. In fact, interventions are most successful when implemented in kindergarten or first grade, Tacker said.

Tacker said she has discovered answers on how to support dyslexic children. The first step is playing to their strengths.

“School may be a struggle and the intensive tutoring interventions may be a challenge,” Tacker said. “While they are getting the help they need, find out what your child is really good at and let him be successful at that.”

Tacker is coaching a 16-year-old boy who is a straight A student and a gifted athlete. “It takes him three times as long to do his homework,” Tacker said. “He reads slowly. For him to be able to take the SAT or college level classes, he needs intervention so he can learn and understand what he reads more efficiently.”

Tacker provides students and their parents with a game plan. She helps dyslexic students discover their “super powers.” She tells her sons and her clients that some of the greatest thinkers, artists, engineers, athletes and performers have been dyslexic, including Walt Disney, Steve Jobs, Steven Spielberg, John Lennon, Anderson Cooper, Albert Eistein and Agatha Christie.

“Every dyslexic has a super power,” Tacker said.

Tacker and her husband have struggled how to handle the labeling of being dyslexic.

“The only way to take the negativity, stigma and ignorance out of this identification is to own it and celebrate neurodiversity. Our kids have embraced their identification as dyslexics,” Tacker said. “We have had long talks about what dyslexia means and how we will support and help navigate their learning path.

“I’ve worked hard to get trained to help them. I’m making it my life’s work to help other families identify dyslexic kids and support their learning,” she said.

“I can’t wait to see how all these kids develop and grow and where their paths lead them. They’re in excellent company and will make us all proud.”